My name is Ellen Maynard, 34, an operations engineer for a solar company in the northern suburbs of Seattle. I live alone in a small house at the end of Maple Lane—a cul-de-sac with eight houses and an old HOA sign prohibiting overnight parking. Across the street lives Walter Harris, a sixty-something widower and former police officer. He mows his lawn on Sundays, flies American flags on holidays, and clears snow to the curb for everyone.

It was a bitterly cold winter. Every night, the wind slithered through the cracks in the door like a hungry cat. I slept late because I was finishing drawings for a solar panel installation on the roof of a warehouse. At around 12:42 a.m., there was a knock on the door, as if someone were using a hammer. I dropped my pen in shock.

I turned on the porch light and yelled, “Who is it?”

“It’s—Walter! Open it, Ellen.” His voice was hoarse, as if he had been running. I opened the door and saw him: flannel robe, slippers on, hair matted with rain. He held a flashlight and a leather notebook.

He didn’t beat around the bush: “Get out of the house now. Take nothing but your phone, wallet, keys. Come back in a week. Listen to me.”

“You can explain—”

“There’s no time.” He lowered his voice, his eyes darting to the living room window. “Don’t turn on any lights. Drive right away, to someone. Motel, friends—anything.”

The way he said it—not frantically—but crisp, clear, as if he were commanding. I saw his hands shaking, but his eyes were alert. Behind him, his window flashed a blue light and then went out. My heart skipped a beat.

“Okay… I’ll go.” I grabbed my wallet, keys, jacket, phone, not even bothering to put on my socks.

As I opened the garage door, Walter added, low as the wind: “Don’t come back for seven days. Don’t answer anyone claiming to be from the utility or the police if they call you back urgently. Someone will try.”

I wanted to ask “Who?”, but he had already retreated into the shadows. I drove the Forester out of Maple Lane, the rear window streaked with rain. The rearview mirror reflected him—standing in the middle of the road, turning the flashlight on three times and then off. What code? I didn’t know. All I knew was that my hand on the steering wheel was cold.

1) Motel, Calls, and a Strange Email

At 1:06 a.m., I checked into the Pinewood Motel by the Route 9 gas station. The night clerk swiped my card tiredly, didn’t ask much. The room smelled of cheap soap, the duvet had old stains. I locked the door and plopped down on the bed.

The first message came from Walter: “Leave yet?”—I replied: “Yes. I’m at the motel. Can you tell me?” No reply.

I called the sheriff—a man named Don Levitt. He listened, half-yawning, half-laughing: “Mr. Harris? He used to be a detective. He’s been a little paranoid lately—camera stuff, petty thefts… You stay there, I’ll have the patrol car over to Maple Lane tomorrow morning.”

I hung up, uneasy. Around 2:19, my inbox dinged: an email from “[email protected]

”—subject: “Line Maintenance Update – Maple Lane Area.” Content: “Residents are requested to vacate their homes between 0:00 and 5:00 to check for electrical leaks. Sorry for the inconvenience.” I scrolled through, puzzled: I’d never seen an electric company send an email after midnight. The footer was sketchy, the logo was blurry, the terms link was broken. I clicked view original, saw the Sender Policy didn’t match—the address was from a free server. My skin crawled.

I texted Walter a screenshot of the email: “You know this?”—Still Seen 2:23, no reply.

I closed my laptop, lay listening to the old heater whirring. Couldn’t sleep.

2) Days 1–2: Unusually Quiet

In the morning, I instinctively returned to the neighborhood—staying far away, not going all the way in. Maple Lane was frustratingly normal: the trash cans were neatly stacked, the car parked in front of house 03 was still covered in mud just like yesterday. Walter’s house was closed and quiet, the curtains drawn. Same with mine. No police tape, no patrol car.

I went into the supermarket to buy some small items and then returned to the motel. That afternoon, I got a break-in notification from my smart lock system: “Front door – Incorrect keypad attempt x3.” At 12:43. I zoomed in on the camera—someone had taped the lens. I could still see a glimpse of a dark coat and beanie. I sent the video to the police hotline; they said they would “put it in the system.”

Monday night, 0:58, unknown number calls: “This is NorthSound Power, we need the resident of 8 Maple Lane to come back to the garage to check the meter.” I ask for the work number, the other person stammers. I tell him to call back during business hours; he hangs up.

I text Walter: “Someone pretending to be power. I’m not home.”—No response.

3) Day 3: Mr. Walter’s House Is Silent

On the third day, I decided to stop by Mrs. Lorna’s grocery store nearby. She scanned the milk code and asked, “Aren’t you going home? I’ve seen a lot of strange cars coming into Maple Lane since the day before yesterday.”

“What kind of car?”

“White Sprinter, temporary license plate. Last night, it parked in front of my house, started the engine for 10 minutes and then left.”

I thanked her and turned around. In my head, I only had time to repeat the word “Sprinter” in white.

In the afternoon, I secretly parked at the end of the intersection and looked into Maple Lane between two rows of cypress trees. Walter’s door was ajar. I called Levitt and reported “theft.” He replied, “I’ll send someone over.”

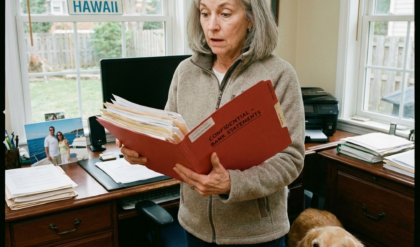

Fifteen minutes later, no one was there. I lost my patience, crossed the street, and gently pushed the door open. It was unlocked. The smell of old paper and coffee was in the house. Everything was too neat: the desk was lined with dozens of USB sticks labeled with dates, the printer, the map of the area with a red circle around my house.

On the table was a handwritten note:

“Ellen—if I don’t have time to say: Don’t go home. They’re using the vacant house as a transit point. White Sprinter van. Shift: 1–3 a.m. In a week, everything will be revealed. I apologize for dragging you into this.”

Signed: W.H.

My heart was pounding. I couldn’t find him; the bedroom was as neat as “unblocked.” The basement was locked. I didn’t dare linger.

That night, I received an anonymous text message: a photo of my license plate and the words: “Go home if you don’t want trouble.” The number was from an Internet messaging app. I called the police. No call back.

4) Day 4: Mail in the Box and the “Fireplace”

On the morning of the fourth day, I stopped by Maple Lane again. I didn’t go into the house—I went straight to the mailbox. Inside was a package in the form of a letter without a stamp, handwritten only: “Elen, open in 7 days—W.” (He missed the l.) Inside was a small key and a piece of paper:

“The wall behind your fireplace. The faux brick on the right, second row. Push and pull.”

I swallowed. I wanted to get in, but I remembered what I had been told. I turned around and drove like I was running from an invisible storm.

That night, at 0:57, another strange number came in: “Miss Ellen, this is Officer Levitt. Come home—your neighbors reported smoke.” “What color is the smoke?” I asked—there was a hum. I said to call 911 and hung up. I called 911; they said there was no fire.

I texted Walter: “They just used the sheriff’s name to trick me into coming home. I made it through the fourth day.”—The screen read Delivered.

5) Day 7: Return

Exactly a week, at 0:30, I parked at the end of the street overlooking Maple Lane. No Sprinter. The moon splits in half. I open my phone, swipe into the home lock app—Offline. I take the key Walter gave me, and slip it through the back door.

The house is silent. I don’t turn on the ceiling light; I just turn on my phone’s flashlight, and stay close to the wall. The living room tile fireplace is as cold as a piece of metal just out of a mold. I kneel down and observe: the second row of tiles on the right has a slightly off-grained tile. I press—click—it sinks, revealing a gap. I pull, and the entire tile protrudes like a drawer. Inside is a black USB, a 1TB hard drive, and an envelope.

Inside the envelope was a handwritten note, written neatly in Walter’s handwriting:

“Ellen,

If you can open this in 7 days, it means I’ve stopped them or at least made them change their schedule. The hard drive contains the camera in front of your house (I’ve wired it in parallel behind the paneling since I helped you upgrade), and the camera I put on the lamppost. The USB has video from inside the garage of house 05—the owner is in Florida for a few months. That’s where they’re transiting.

I’ve reported Detective Marisol Vega to the county—don’t report Levitt. Don’t trust Levitt. The Sprinter is C93- (I can write 3 characters). The group used Evergreen HVAC jackets as cover. Don’t come back at night. Meet Vega, give them everything.

Sorry I can’t explain at night. Trust me one last time. —W.”

I hear the car rattling in the distance. It’s not a Sprinter. I stuff everything into my bag, leave the house before 1 o’clock.

6) Marisol Vega

The next morning, I went to the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office and asked to see Detective Marisol Vega. She appeared in a leather jacket, her black hair tied back, her eyes sharp but not cold. “Ellen Maynard?”—She held out her hand.

I put the USB and hard drive on the table. “Walter Harris’s. He said he’d see you.”

Vega didn’t hide her wariness. “Harris… what channel did he contact you through?”

“Handwritten. He’s missing.”

Vega lowered her voice: “He’s not missing. He’s in the county’s witness protection—injured, but okay. Before he went in, he gave me a bunch of stuff like this, saying, ‘Wait seven days, you’ll have a second witness.’ I guess it was you.”

I breathed a sigh of relief.

“But why did you say I don’t trust Levitt?” I asked.

Vega didn’t answer right away. She plugged the hard drive into her computer. The screen was filled with folders by date and time. “Look at this,” she said, opening the clip 00:52–01:31 AM, the first. The screen showed a white Sprinter parked at the curb in front of my house. Two figures in Evergreen HVAC jackets quickly opened the back door and carried a carton into the garage of house number 5. A moment later, a third person appeared: the HOA head—Mr. Kendrick—holding a clipboard, looking around, stuffing something into the porter’s pocket. The clip ended with headlights hitting Mr. Walter’s window—someone flashing the blinkers three times.

“That’s the signal he gave me,” I said, remembering the first night.

Vega pulled up another clip: 01:08–01:12 AM, 3rd. The lamppost camera picked up the license plate as the Sprinter backed up. Frame paused: C93-7FQ. Vega quickly tapped into the system. “Vehicle registered to Evergreen Heating & Air, owner Jonah Pike. This company has been fined for illegal connections.”

“Is Levitt involved?” I asked.

Vega pursed her lips. “Levitt closed two break-ins on Maple Lane for ‘lack of evidence.’ Mr. Harris tried to give him the data but was told off. The old man wouldn’t let go, so they took action—the night you left, one of them was at your door. If you had opened it, you could have been forced to sign a ‘consent’ to be inspected, and then he would have sneaked stuff into your house.”

“What stuff?”

Vega looked at me: “Fentanyl. Or money. Or both.”

The skin on the back of my neck went numb.

“We need inside evidence,” Vega said. “And you just brought it.”

7) Feint

Vega suggested setting up a feint. The plan was simple: she’d have someone secretly watch Maple Lane, while I stayed at the motel, turning off my phone at night. On the eighth night—because they had a habit of shifting schedules when they suspected someone was following them—Vega would have a pickup truck pull up on Maple Lane like an unsuspecting neighbor, forcing them to reveal themselves.

That night, at 0:44, Vega texted “in.” I sat at the motel, my heart pounding, my arms hugging my knees. She updated me with a short text: “Sprinter over. 2 people. HOA Kendrick showed up. Another car…”—Then it was gone.

I just saw a call coming in. Levitt’s number.

I hesitated, picked up.

“Ellen, I know you’re working with the county,” Levitt said, his voice not as lethargic as it had been the last few times. “You missed the point. Harris is a delusional person. Don’t let yourself be used as a tool.”

“I’m calling with Detective Vega,” I lied. “Say what you want to say to both of us.”

Silence on the other end for a second—then a faint smile. “You’re smart. Good luck.” Hang up.

Two minutes later, the phone rang: Vega. “Done. Caught red-handed. Kendrick, Jonah Pike, two more. Cash in the car, two guns, a few bags of powder. Can’t reach you because I’m in the arrest car. Are you okay?”

I laughed, then… cried. I’d been so tense for a week, I let it all go.

8) Unlock

In the morning, Vega called me to the scene. Maple Lane was full of county police cars, Levitt’s car was nowhere to be seen. Number 5 had a warrant on it. The white Sprinter was towed away. HOA Kendrick sat in the car, handcuffed, his face ashen.

Vega turned to me: “Do you want to come in?”

I nodded.

The door opened, smelling of dry dust and old wood. There was no sign of disturbance—they hadn’t had time to come in. I sat down on a chair, opened the window to let in the cold air. Suddenly I saw the fireplace—the fake brick I had pulled. I replaced it, pushed it in. Everything was back to normal, except the person in this house had changed.

Vega stood with his hands clasped: “If you don’t believe the old man, I’ll probably see you in the interrogation room now as… the person whose house is a storage room.”

I swallowed my tears. “Where is he? I want to see him.”

“Maybe this afternoon.” Vega smiled slightly. “He told me you were ‘the kid who listened in time.’ He was stubborn. But he saved this whole street.”

9) Walter

In the afternoon, I went into the hospital room in the witness protection area. Mr. Walter was lying on the bed, his hand bandaged, his face a little swollen. The same eyes—ashen gray as a rainy day.

“Ellen.” He nodded. “You listen to me. Good.”

“Why don’t you explain?” I asked, annoyed but grateful.

“Because if I do, you’ll ask more, and stay to listen,” he replied, breathing softly. “Some things can only be said after people are in a safe place. I’ll only dare touch them after you’re gone.”

I pulled my chair closer. “Are you hurt…?”

“Got a gun butt, broke a bone in my hand,” he shrugged. “I’m old, but I’m not done yet.”

I told him about the USB, the hard drive, Vega, Levitt. He snorted: “Levitt takes money from HOA Kendrick. He’ll try to clean it himself, but Vega’s team trusts him. You… change the locks, change the combination, move if necessary.”

“I think I’ll stay.” I looked out the window. “Over the past week, I’ve learned I like this street. And I like knowing there’s a stubborn old man next door.”

He chuckled, then became serious: “Ellen… there’s one thing.” He looked down at his bandaged hand. “I couldn’t save my wife. That year, I came home late from a case—she collapsed in the kitchen, had a stroke. I carried that—that I was late—for twenty years. That night, when I knocked on your door, I thought: don’t be late again.”

I couldn’t help myself, I stood up and hugged him—an awkward hug, through the thin blanket and the smell of rubbing alcohol.

“Thank you,” I said to the air.

“Don’t thank me,” he muttered. “Just…don’t ignore your intuition. And, get a dog. A good dog will bark at the right time.”

10) The Days That Followed

The Evergreen HVAC case hit the local paper: “Cybers Moving Cash and Drugs Masquerading as Contractors.” Kendrick was accused of complicity; Jonah Pike’s company had its license revoked. Levitt was investigated internally for negligence—and later prosecuted for bribery (Vega added via text, with an emoji not entirely suited to detective work). Maple Lane was back to normal—except now everyone was locking their doors and watching cameras more.

I fixed the fireplace, installed a more secure fake brick. I offered Walter dinner on his left hand, which he had just removed from its splint: roast chicken, mashed potatoes, and fried green beans. He told me I’d cut the potatoes too big; I argued—and then I laughed because I argued like a child.

“Ellen,” he said when we were done, “there are two kinds of people in this world: those who need a reason to act, and those who can act before they know why. You’re the second kind when you need one. That kind survives well.”

I asked, “Do you regret not telling me everything that night?”

He thought for a moment: “Yes. And no. If I had told you, you could have stayed to help, and then they would have put a box in your garage right in front of you with a ‘consent to check’ note. I needed you to disappear—to give them a missing link. Sometimes when you save someone, you don’t need to explain. You just need them to trust you enough to run.”

I nodded. The first image of that night popped into my head: a flashlight flashing three times. A private SOS code between two neighbors.

11) Conclusion

In my mailbox now was a handwritten card:

“If you see anyone wearing an Evergreen uniform around here—call me first, then 911. —W.”

At the end of Maple Lane, the wind still whipped through the cypress trees like a playful cat. On dark nights, I’d open the window and listen to Walter’s TV—a black-and-white movie, the old actor’s voice blaring. I set my alarm for 0:42—not to wake me up, but to remember: someone woke me up at the right time one night, and I listened.

Last week, I went to the rescue and brought home an ash-colored shepherd mix, named Pixel. The first night, at 1:05, Pixel suddenly perked up his ears and hissed softly. I looked through the camera: a dry leaf had rolled across the steps. I laughed, picked him up, and said, “It’s okay.”

It didn’t end with a siren or a flash of red and blue lights. It ended with a new routine: checking the door locks, ignoring suspicious calls, saving Detective Vega’s number to the top of my contacts, and sharing the road with a stubborn old man who knew how to knock at the right time.

If anyone asks, I’ll tell this story as a simple lesson: When someone you trust knocks on your door in the middle of the night and says, “Get out—come back in a week,”—don’t argue. The distance between paranoia and premonition is sometimes just a life.